NOTES ON DIRECTING by Gary De Mattei

During the summer of 2022, I directed and choreographed two shows (at once) for the Lyric Theatre of San Jose. Here are my “Notes on Directing” published in The Patter Post, the newsletter of Lyric Theatre, the performing arm of the Gilbert and Sullivan Society of San Jose.

THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE

(PHOTO: The Stanley Sisters and Orchestra, Hammer Theatre, San Jose, Summer 2022)

Former New York Times theatre critic, Ben Brantley, when reviewing director Ian Rickson’s transcendent 2008 Royal Court Theater production of Anton Chekhov’s, The Seagull, wrote,

“One of the most wonderful paradoxes of the theater is deeply unhappy people can generate profound happiness in audiences allowed to eavesdrop on their lives.” I do believe with The Pirates of Penzance and Into The Woods, we not only have two productions chocked full of unhappy people— with absurdities at their core rivalling many a Samuel Beckett play— but we also have two productions that will leave audiences with the feeling that— after each of their respective two-and-a-half-hour-stage-trafficking— someone must’ve been pumping nitrous oxide through the ventilation system of the Hammer Theatre Center.

A Chekhovian mantra that I adhere to religiously is, “The role of the artist is to ask questions, not answer them.” Depending on whether or not I’m directing a play, musical, operetta, or a performance art piece in a fountain at a public park — my work as a theatre artist begins with reading the text over and over again in an attempt to identify the hidden questions posed by the storytellers. I then like to inject said questions with helium so they not only float above my head throughout the production process, but also above the audience’s heads during the entire performance.

When I’m in front of a group of actors about to start, say, rehearsals for The Pirates of Penzance, I’d probably open with something the great theatre and film director, Mike Nichols, told one of my teachers, and they, in turn, told it to me, and now I’m telling it to you, dear reader, “Acting is you….in different circumstances.” So, the pressure is off, you don’t have to pretend to be anyone else, just be yourself and play the circumstances of the character.

Begin your character development with discovering your circumstances. For example, where are you? How does your location change your own personal experiences? If you’ve never been to 19th century Penzance, your research will show you that Penzance is a lot like Carmel by the Sea. And if Carmel doesn’t work for you, come up with a substitution that does (Key Word: Substitution); a place you’ve actually been to that gives you the same feeling of a sleepy affluent community by the shore. Maybe for you it isn’t Carmel, maybe for you it’s The Hamptons. If so, you’re probably rich. And if that’s the case, perhaps you’d like to consider making a tax-deductible contribution to Lyric Theatre of San Jose, or, at the very least, become a member. But I digress. Wherever it is, think of Penzance as having been invaded by members of a privileged class masquerading as a gang of thieves in an era where certain groups of people are struggling for equal rights and income equality.

Yes, the objective of our production of The Pirates of Penzance is to give our audiences a good time while hitting all of the right notes, which also include the acting notes. And, maybe, while we’re at it, we may leave you with a renewed faith in a community theatre dedicated to producing operettas that spoof Victorian love, respectability, and the case for child protective service agencies. Not to mention that all too terrifying —and often dangerous— SENSE OF DUTY, as presented to you, in this case, by a wacky band of wannabe buccaneers, led by a charismatic self-appointed King, Richard, and his de facto ward, Frederic, who, when just a little Freddie, was literally stolen from his father by the trusted nanny, Ruth, who, arguably, is the real pirate of the group that some feel should have the key thrown out to sea immediately after she’s been locked up for life, so that her stalking of poor Fred will cease, and he can get on with living happily ever after in therapy with Mabel, the spontaneous ingenue with a mind of her own who isn’t afraid to take a stand center stage and hit all the high notes, which couldn’t be possible without her backup band, The Stanley Sisters in Distress…not to mention painful corsets. And speaking of bullet proof vests, don’t forget that lovable crew of cowardly cops led by their shrinking violet in blue, Edward, the Sergeant of Police. And last, but certainly not least, our all-time family favorite, that very model of a modern Major General, Stan The Man, who lovingly epitomizes W.S. Gilbert’s supreme credo— “That of treating a ridiculous notion with the utmost seriousness.”

Although there is much debate about this among Gilbert and Sullivan scholars, purists, fanatics, fascists, and such— we are setting our version of The Pirates of Penzance on 1 March, 1881. In short, we aren’t updating the time period of the piece to a present-day pool party at a fraternity house. (Which is not a bad idea…maybe next time.) No, we are saying that Frederic was born 21 years earlier, on 29 February, 1860. His 21st birthday will occur 88 years after birth, in 1948. Frederic is not at all good with sums, so the quick figuring he does in his head, stating he’ll be of age in 1940, is off by 8 years. This we shall attribute to the fact that he’s been at sea most of his life and his Nanny was relaxed in her homeschooling duties. She may indeed be a Maid of All Work…except when it comes to math.

The Pirates of Penzance has one of the silliest plots ever created to one of the most ingenious musical scores ever written, with enough “borrowed” operatic themes and motifs to make Andrew Lloyd Webber blush. All in support of underscoring unrequited love, parental abandonment, and a privileged class who has no time for respectability because they’re too busy dressing up in Halloween costumes, waving homemade flags, and storming the steps of Penzance City Hall. And after all of that is said and done, for me, The Pirates of Penzance also asks the burning question— Why poetry? That’s the balloon that floats above my head throughout the entire production process.

Late in the first act, while watching one of the daftest scenes ever constructed on any page, the show stops and we are brought out of the comedy and into what I consider to be the soul of the piece,

“Hail, Poetry, thou heaven-born maid!

Thou gildest e’en the pirate’s trade:

Hail, flowing fount of sentiment!

All hail, Divine Emollient!”

It’s a wonderful five-part harmony moment reminding one that Arthur Sullivan wrote wonderful hymns, like, “Onward Christian Soldiers”; and that as silly as the show is, Sullivan was a composer to be reckoned with, and steal from. And more importantly, a reminder that what we are witnessing is a work of musical and poetic art as crafted by a group of talented folks who got together and said, We must not forget our sense of duty as artists, which is to not only entertain, but to nurture and enrich the human experience. And theatre, when it is done right— when there is harmony on the stage, as well as in the component parts— well, then we as artists have done the work, which is best explained in the words of the late, great Beat Poet, Alan Ginsberg, who, when asked the question, “What’s the work?” replied, “To ease the pain of living. Everything else, drunken dumbshow.”

And some of us forget about poetry until we need it and thanks to groups like Lyric Theatre of San Jose— who have been around since 1972 producing poetry of one kind or another, we can experience these alchemical moments together in the dark. Most of the time we aren’t too concerned with Ginsberg’s poems, or W.S. Gilbert’s poems or anybody else’s poems, until something tragic happens, like a pandemic. Or maybe somebody very close to us has shuffled off this mortal coil, and we are so heartbroken the only thing that will help us make sense of it all are the words of Dylan Thomas, beseeching us to “rage against the dying of the light”. Or the opposite— something great happens— one enchanted evening we may see a stranger across a crowded room, and after we’ve dropped our N-95 masks, we fall madly in love with them. And we build a life together, as artists living in New York City. And then we each get jobs— one acting in Wisconsin, the other directing The Pirates of Penzance and Into The Woods in California. And the work is good, but the feeling apart is bad, and too hard to explain over Zoom. So, before you lay your head on her pillow filled with organic buckwheat hulls, you reach for your pocket sonnets and post one of them on Facebook. And you tag her in it, and hope when she wakes she’ll know how you feel without her.

“Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travel tired;

But then begins a journey in my head

To work my mind, when body’s work’s expired:

For then my thoughts–from far where I abide–

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness which the blind do see:

Save that my soul’s imaginary sight

Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,

Which, like a jewel hung in ghastly night,

Makes black night beauteous, and her old face new.

Lo! thus, by day my limbs, by night my mind,

For thee, and for myself, no quiet find.”

— William Shakespeare, Sonnet 27

#HailPoetry

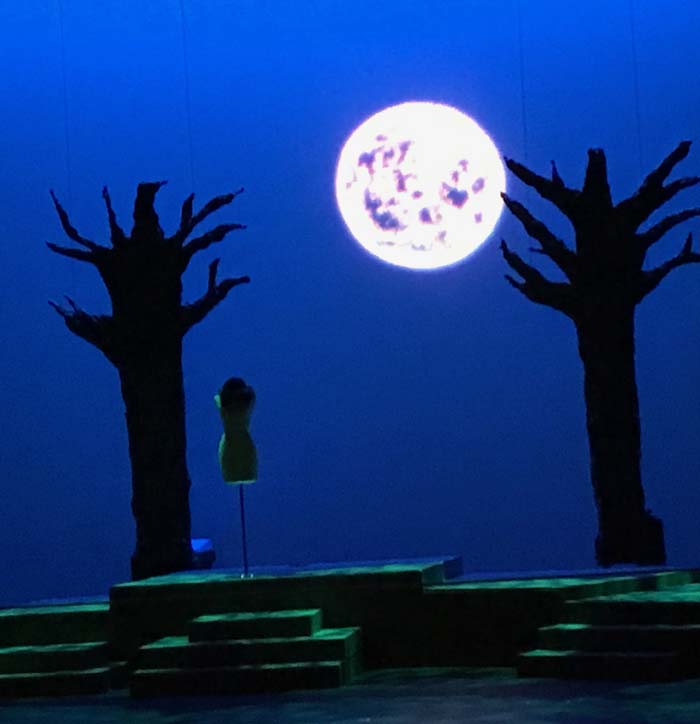

INTO THE WOODS

By now— thanks to the Disney film adaptation of the Broadway musical, directed by Rob Marshall, that was released in 2014, and grossed over $213 million worldwide— everyone has seen Into The Woods, the Stephen Sondheim, James Lapine adaptation of the Grimm Fairytales. The stage show has been printing money for the New York licensing house, Music Theatre International, since they acquired the rights at the end of the last century. Since then, the show has been done all around the globe, and at every level— from one-act Junior versions featuring children of all ages who do not listen to their directors, to full-length stripped down off-Broadway versions that just use a ladder and an upright piano on stage, to the most recent ENCORES revival at New York City Center featuring a star-studded cast that included Sara Bareilles as the Baker’s Wife, Denée Benton as Cinderella, Neil Patrick Harris as the Baker, Heather Headley as the Witch, and a choir of singers who lined the aisles of 2,750 seat New York City Center theatre during the finale.

The Encores version was also the first professional New York production of “Woods” produced without Mr. Sondheim’s physical form in the world. For some of us who grew up doing theatre over the past 40+ years, and who credit Stephen Sondheim with the reason we fell in love with musical theatre in the first place, it’s safe to say that at present, and because of his loss, we all feel a little like orphans. I, like so many others who’ve made their life’s work the theatre, especially the Musical Theatre, have grown up with Stephen Sondheim in my world. And through his art, his books, his videos, and on those rare occasions when he’s been sighted at the theatre or in a Manhattan restaurant, I have adopted him as not only one of my guides, but also as a surrogate parent. My first thought after his passing was, “How will I survive?” So, I went straight to his poetry and after reading several passages from Sweeney Todd aloud, about the world being a great black pit filled with people who are filled with… sadness because Stephen Sondheim is gone, I found this bit of text from Into The Woods to calm me down:

“Sometimes people leave you

Halfway through the wood

Others may deceive you

You decide what’s good

You decide alone

But no one is alone”

So, as I do when I’m about to direct any production— be it a play I’ve never seen before or a classic I’ve seen hundreds of times like Into The Woods — I research all there is to research about why the creators spent years and years writing and re-writing and workshopping and out of town try-outing, etc. And if there’s any interviews from the creators on their arduous process, I devour them like Little Red devours the freshly baked sweets in the opening number. And thanks to the wealth of material written and recorded by the creators of Into The Woods, I was able to have several visits with Mr. Sondheim, and I listened to his cautionary tale about doing this show— which contain several traps— because I wanted to get it right, for him. Because for me, Stephen Sondheim is the real star of the piece. And I think more than anything else, a director’s job is to do no harm to the material. And in this case, that also means, Do no harm to Stephen Sondheim. So, I listened carefully to my master’s voice. And I took notes, and here they are, in no particular order of importance.

— First of all, the master said, Into the Woods is a show about a group of people who have various wishes and during the course of the show they get their wishes but in so doing upset the natural order of things and have to pay for it in the second act, and become a community and merge their individual wishes into a community wish and thereby save the world…so to speak.

— Start with The Grimm Fairy Tales. Go back to them. Read them. They are short by nature. In the Grimm version Cinderella goes to the ball three times, she can’t make up her mind.

— It is very important to keep the show bouncy; keep it moving.

— Little Red has the title number in the show.

— Jack is a guy who steals, if you look at Jack through the Giant’s point of view, he’s a villain— he comes to your house, steals all of your goodies and then kills your husband. That’s the attitude of the Giant. Jack goes up to the Giant’s house three times.

— Little Red starts out innocent and becomes a blood thirsty killer. In the Grimm she goes back into the woods a second time and kills another wolf.

— The Witch is the most direct and the most honest— you can’t always equate nice with good.

— Act One is about the individual. The second act is about community where we find out what the consequences are of the “individual mindset”.

— Musically speaking, The Witch’s five notes (five items) are a reflection of a plot point. The Witch’s section is sometimes referred to as a rap section. “It is not rap, it’s patter.” — Stephen Sondheim

— The function of the opening number is exposition; you might assume everyone knows that Cinderella has a grave of her mother in the woods. Treat this as if no one has heard these stories before. The witch’s story has to be covered in some detail and this is where diction becomes very important and finding places to breathe becomes very important. The Witches part is the most important in the opening number and diction is the key.

— The Five Notes: the function of these notes are the five magic beans (of the six), these five notes show up when it has to do with the beans.

— The opening number should have joy.

— The Witch works best when she’s played scary; that she holds powers that effect.

— Cinderella is the toughest because she’s so familiar. The notion that Cinderella talks to birds, she’s a little out of the ordinary, she’s a little spaced out, a little ditzy, she’s not apple pie. The other thing is that she’s not just good, it’s boring to be good. She pulls too hard on her stepsisters hair. She’s not just a good person. She’s real.

— Jack is the dreamer, not dumb; he is in his own world.

— Jack’s mom wants to keep Jack a child, otherwise she wouldn’t know what to do.

— Rapunzel is a kid who’s been locked in a tower for 17 years, so that speaks to her character. She definitely has a neurosis so anything you can bring out there is good.

— The Baker and his Wife are the outsiders, they are sort of like that couple from Brooklyn who’ve drifted into the woods. They stand in for the audience. They find themselves in the forest with witches and spirits running around. They are the least extraordinary of the group. They’re caught in the circumstances and that is basically the humor of the show.

— The Princes — you can go any number of different ways with these two. They’re pampered and they’re spoiled but don’t make them an easy target; find their humanity especially with Cinderella’s Prince in the second act.

— The Mysterious Man — he’s a father and not well drawn. He stands in for that kind of parent we have that we don’t know and always wish to touch base with.

— “The Witch is a bad lady, someone you don’t want as a neighbor.” — James Lapine

— Little Red is wide-eyed innocent until she meets the wolf. She makes a nice transformation.

— Look at your character’s transformation. When do they change? What’s that called?

— Parents tend to be distant.

— Stepsisters and Stepmother go against the obvious; don’t play them mean. Make them grand and beautiful, their meanness will come through.

— The Narrator is a curious character, you can play him professorial or Jungian he should be someone we want to listen to, someone we want to trust our future to, he has power.

— Agony— watch out for this number it has a trap. The princes are rivalries, they are caught in their own fantasy, but they’re essentially saying, “I’m suffering more than you. My agony is far more painful than yours.” It isn’t just the unattainable girls, it’s their rivalry, it’s their contest; it’s their own personal pain. This happens a lot with siblings.

— No More is a father/son song, a song that has no relationship. Don’t keep it self-pitying, it’s a song that is a determination for the Baker to go back. No More means he is not going to take any more of the destruction and he’s saying we all have to act together as a community. That is what makes him go back.

— No One is Alone is a quartet for the four survivors, the older and the younger survivors. Cinderella changes the most. She becomes responsible. This is a parent/child song and should be thought of in that way. The point is this is not the kind of alone we’re talking about, it’s about being connected with each other, we all need each other. Musically speaking, this is where the “bean theme” finally becomes calm and it’s at its most simple harmonically even though they’re singing against it. Think of this “bean theme” as being resolved here. And, therefore it will feel like the story is being resolved. So, the story is resolved because the story is the “bean theme,” the inversion of the “bean theme” is “People make mistakes.”

— Above all, focus on the intelligibility, the words, the intentions of the songs. What really matters is the audience understands the words.

— The end is “I Wish We Would All Live Happily Ever After”.

#iWish